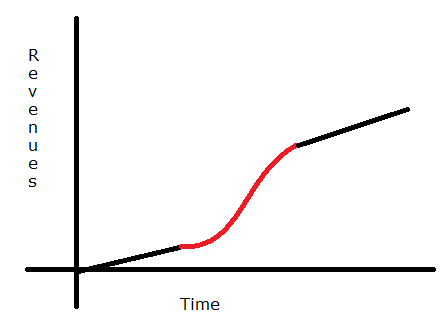

The growth of a new company usually consists of one short period of high growth preceded and followed by rather long periods of steady growth. Sometimes there might be more than one period of high growth, but for most companies, it is that one period when there is a point of inflexion and growth goes to a new trajectory.

Now, my point is that if you want to raise venture funding, you better do it when you think you are on the cusp of one such inflexion. Usually points of inflexion are associated with some increase in “leading” investment, and a small chance that the company will get on to a new trajectory, and a big chance that the company will go under.

If you look at the picture here, the beginning of the red region is the state where you need to get venture funding. The thing with the black regions is that irrespective of how you fund those, at best you can expect steady growth. Now, venture capital funds, the way they are structured, are not set out to fund steady growth. The way venture funds make money is when one out of a number of their investments makes shockingly great returns, while the rest go under. They are not in the business of funding steady returns.

Hence, when they fund your company they value you assuming that in case your company is successful there will be steep growth, which will enable them to recover their investment. And if your company is in steady growth phase, it is never going to be able to do that. And you will have a case of your investors pushing you to do more or something different from what you had planned doing. The problem here lies in the fact that you raised the wrong kind of funding!

In times like this or at the turn of the millennium, when venture capital is big, it can sometimes become the preferred mode of fundraising for a lot of companies. The problem, however, is that most of them don’t realize that venture funding is probably not the best form of funding for them at their size and scale, and then get weighed down by investors.

On a similar note, you should go public once you know that there are no really big points of inflexion coming up, and that your company is set on a path to steady growth. Again that follows from the fact that investors in the stock market (where they pick up tiny shares in each company) are usually in it for long-term steady growth. And if you happen to take undue risks and they don’t pay off, your stock will get hammered unnecessarily.