We’ve spoken about Thomas Schelling’s segregation model here before. The basic idea is this – people move houses if not enough people like them live around them. A simple rule is – if at least 3 of your 8 neighbours around you aren’t like you, you move.

And Schelling’s insight was that even such a simple rule – that you only need more than a third of neighbours like yourself to stay in your place, when applied system wide, can quickly result in near-complete segregation.

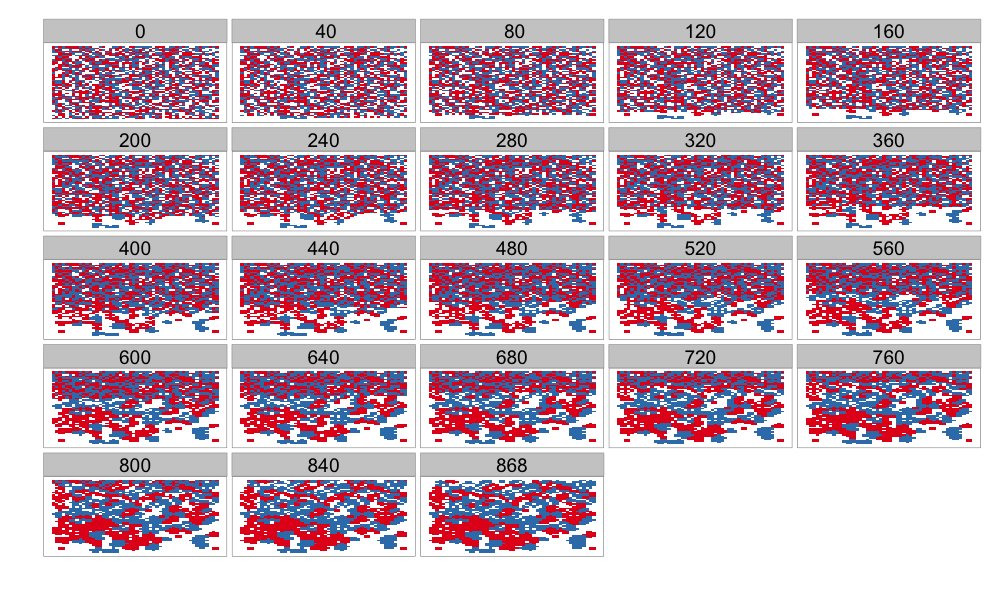

I had done a quick simulation of Schelling’s model a few years back, and here is a picture from that

Of late I’ve started noticing this in retail as well. The operative phrase in the previous sentence is “I’ve started noticing”, for I think there is nothing new about this phenomenon.

Essentially retail outlets want to be located close to other stores that belong to the same category, or at least the same segment. One piece of rationale here is spillovers – someone who comes to a Louis Philippe store, upon not finding what they want, might want to hop over to the Arrow store next door. And then to the Woodland store across the road to buy shoes. And so on.

When a store is located with stores selling stuff targeted at a disjoint market, this spillover is lost.

And then there is the branding issue. A store that is located along with more downmarket stores risks losing its own brand value. This is one reason you see, across time, malls becoming segmented by the kind of stores they have.

A year and half back, I’d written about how the Jayanagar Shopping Complex “died”, thanks to non-increase of rents which resulted in cheap shops taking over, resulting in all the nicer shops moving out. In that I’d written:

On the other hand, the area immediately around the now-dying shopping complex has emerged as a brilliant retail destination.

And now I see this Schelling-ian game playing out in the area around the Jayanagar Shopping Complex. This is especially visible on two roads that attract a lot of shoppers – 11th main and 30th cross (which intersect at the Cool Joint junction).

These are two roads that have historically had a lot of good branded stores, but the way they’ve developed in the last year or so is interesting.

I don’t know if it has to do with drainage works that have been taking forever, but 32nd Cross seems to be moving more and more downmarket. A Woodland’s shoe store moved out. As did a Peter England store. Shree Sagar, which once served excellent chaats, now looks desolate.

The road has instead been taken over by stores selling “export reject garments” and knock down brands. And as I’ve observed over the last few months, these kind of shops continue take over more and more of the retail space on that road. In that sense, it is surprising that a new Jockey store took over three floors of a building on that road – seems completely out of character there. I expect it to move in short order.

I must mention here that over the last few years, the supply of retail space in Jayanagar has exploded, and that has automatically meant that all kinds of brands have space to operate there. It was only natural that a process takes place where certain roads become more upmarket than others.

Nevertheless, the way 30th cross (between 10th and 11th mains) and 10th main have visibly evolved over the last year or so is rather interesting.