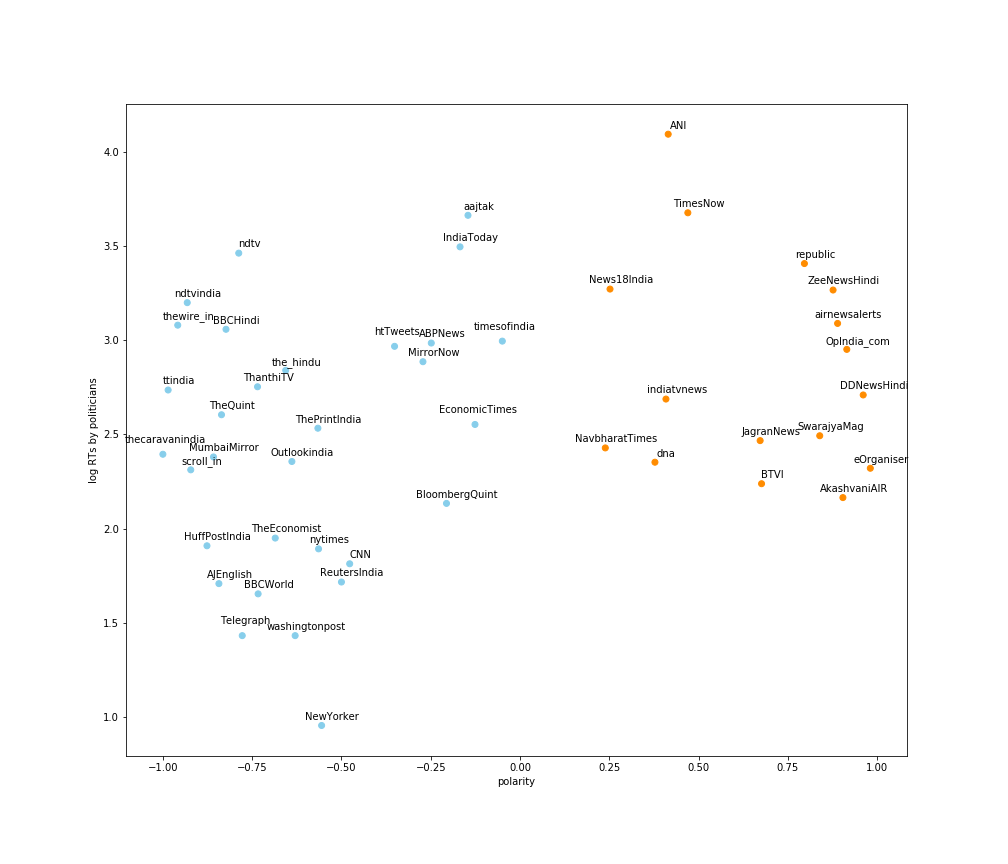

I’ve written earlier about how once news media became dependent on subscriptions, it started becoming partisan. Thinking about it, it is not particularly correct.

If we think of the traditional (physical) newspaper, it was seldom given away for free (when I lived in London I would pick up free copies of the Evening Standard on days when I needed to line my compost bin). Traditional newspapers relied (and still do) on a combination of subscription and advertising for their revenues.

In that sense, what the New York Times does now (read this nice interview with its outgoing CEO) is basically a digital transformation of what it has been doing for over a hundred years – make money off a combination of subscription and advertising.

So if the business model was the same, why did the online New York Times differ from its previous avatar and become politically partisan? Because the nature of advertising changed.

Nowadays I have this favourite theory that everything is a bundle (maybe I should write my next book about this?).

Everything in life (and business) is a bundle

— Karthik (@karthiks) August 3, 2020

You can consider this post to belong to this meme.

The traditional newspaper, if you think about it, was a collection of news and advertisements all bundled together. While you could choose what part of the paper you wanted to consume, when you went to a page you would inevitably scan all the headlines. And whether you liked them or not, you would actually eyeball all the advertisements.

The important thing to note is that the paper was a physical product and what advertisement the reader was shown did not depend on that person at all. Whether you were a raving communist or a slaveholder, you would be shown the same set of advertisements.

This meant that physical newspaper advertisements were (and still are) dominated by mass products that were aimed at everyone. And since these advertisements were usually paid for based on an estimate (sometimes highly inaccurate) of how many people saw them, the newspapers wanted to maximise the eyeballs. This meant not taking any extreme political stances, and keeping all parts of the political spectrum onside.

What changed with the move to digital was that this bundle containing the news and the advertisements broke down.

With advertising being sold through data-driven ad exchanges, it was now possible to show different advertisements to different people. And with advertisements now dependent on your search and browsing history (apart from your political preferences), it was effectively personalised. The New York Times did not need to directly sell advertising any more. All they needed to do was to sign a contract with Google or Facebook or both. Job done.

Digital advertising doesn’t make sense for mass brands. Rather, it is highly likely that the availability of data will mean that they will frequently get outbid by highly targeted brands. So whether mass brands wanted to advertise in the New York Times became a less important decision. The paper had no compulsion to be politically neutral any more.

And once their early set of subscribers showed a marked preference for one kind of politics, it made sense to them to go after the subscription dollars of this audience rather than the already uncertain dollars of potential subscribers that preferred another kind of politics. And then there as a self-reinforcement cycle.

Media can crib as much as they want about the likes of Google and Facebook taking away their money. They can lobby, like they have done in Australia, to “levy a google tax“. People can crib about media having become biased.

However, we need to remember that all this mess started with the unmaking of a bundle – once news and advertising had been separated, there was no turning back.