A few months back I stumbled upon this dataset of all voters registered in Bangalore. A quick scraping script followed by a run later, I had the names and addresses and voter IDs of all voters registered to vote in Bangalore in the state assembly elections held this way.

As you can imagine, this is a fantastic dataset on which we can do the proverbial “gymnastics”. To start with, I’m using it to analyse names in the city, something like what Hariba did with Delhi names. I’ll start by looking at the most common names, and by age.

Now, extracting first names from a dataset of mostly south indian names, since South Indians are quite likely to use initials, and place them before their given names (for example, when in India, I most commonly write my name as “S Karthik”). I decided to treat all words of length 1 or 2 as initials (thus missing out on the “Om”s), and assume that the first word in the name of length 3 or greater is the given name (again ignoring those who put their family names first, or those that have expanded initials in the voter set).

The most common male first name in Bangalore, not surprisingly, is Mohammed, borne by 1.5% of all male registered voters in the city. This is followed by Syed, Venkatesh, Ramesh and Suresh. You might be surprised that Manjunath doesn’t make the list. This is a quirk of the way I’ve analysed the data – I’ve taken spellings as given and not tried to group names by alternate spellings.

And as it happens, Manjunatha is in sixth place, while Manjunath is in 8th, and if we were to consider the two as the same name, they would comfortably outnumber the Mohammeds! So the “Uber driver Manjunath(a)” stereotype is fairly well-founded.

Coming to the women, the most common name is Lakshmi, with about 1.55% of all women registered to vote having that name. Lakshmi is closely followed by Manjula (1.5%), with Geetha, Lakshmamma and Jayamma coming some way behind (all less than 1%) but taking the next three spots.

Where it gets interesting is if we were to look at the most common first name by age – see these tables.

Among men, it’s interesting to note that among the younger age group (18-39, with exception of 35) and older age group (57+), Muslim names are the most common, while the intermediate range of 40-56 seeing Hindu names such as Venkatesh and Ramesh dominating (if we assume Manjunath and Manjunatha are the same, the combined name comes top in the entire 26-42 age group).

I find the pattern of most common women’s names more interesting. It is interesting to note that the -amma suffix seems to have been done away with over the years (suffixes will be analysed in a separate post), with Lakshmamma turning into Lakshmi, for example.

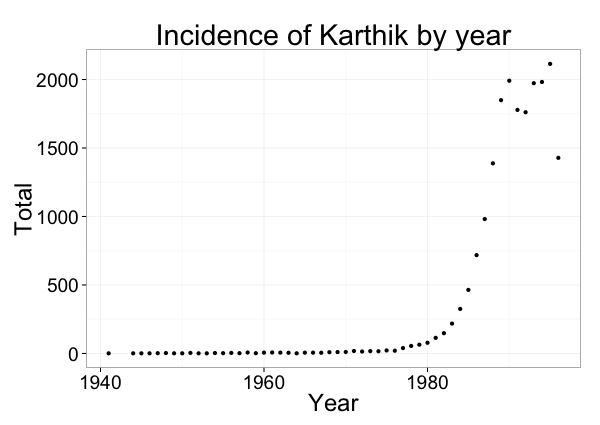

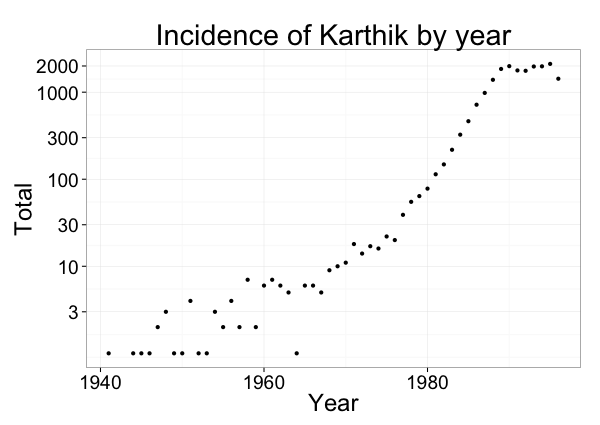

It is also interesting to note that for a long period of time (women currently aged 30-43), Lakshmi went out of fashion, with Manjula taking over as the most common name! And then the trend reversed, as we see that the most common name among 24-29 year old women in Lakshmi again! And that seems to have gone out of fashion once again, with “modern names” such as Divya, Kavya and Pooja taking over! Check out these graphs to see the trends.

(I’ve assumed Manjunath and Manjunatha are the same for this graph)

So what explains Manjunath and Manjula being so incredibly popular in a certain age range, but quickly falling away on both sides? Maybe there was a lot of fog (manju) over Bangalore for a few years?