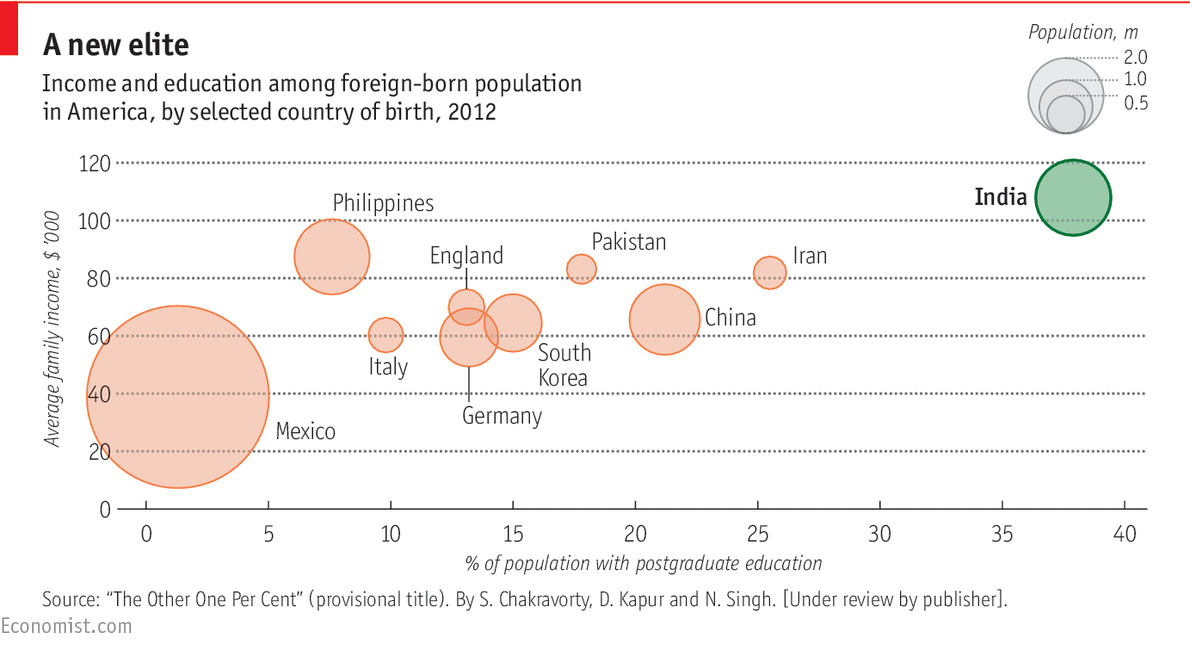

There is this one chart from the Economist that has been doing its rounds over the interwebs over the last few days:

Basically it shows that Indian Americans are much more accomplished academically and professionally compared to other immigrants. And there are many theories floating around as to why Indians are so successful.

The answer, however, is rather simple – selection bias. Migrating from India to the US was an extremely difficult task till the 1960s – there were some quotas that the US had for immigration under which the Indians had nothing. And when Indians did finally start migrating in the 1960s, it was mostly for education.

Most people who migrated from India to the US even in the 1960s and 70s did so to go to graduate school. And this meant that they already had 16 years of education in India, which either meant an engineering or medical degree, or a masters in one of the other fields. So basically most Indians migrating to the US were highly accomplished already.

And considering the kind of foreign exchange controls imposed by the Indian government, the only Indians who could afford to go to the US for an education were those that received a fellowship or support from their universities. Thus increasing the seelection bias! (Now that I’ve mentioned foreign exchange controls, you should listen to this song, which was apparently meant to parody such policies)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PS_fF82PYDc

Yes, you had the odd Patel without much education who made it to open a “Potel” (Patel run Motel), but that is probably the reason that the Indian bubble in the above chart is not farther out!

So that Indians have done better than other migrating communities in the US is not about innate Indian intelligence, or innate Indian ability to work hard, or because the Americans took in the Indians much better than other nationality. It is simple selection bias, based on tight immigration controls and tight emigration controls and stupid foreign exchange policy on the part of Indian government (which, at one point of time, only allowed citizens to take out eight dollars from the country).

To illustrate this point, look at the country that is “second” (quotes since we are looking at two dimensions here, so second is subjective) in this list – Iran.