I’m writing this five minutes after making my wife’s “coffee decoction” using the Bialetti Moka pot. I don’t like chicory coffee early in the morning, and I’m trying to not have coffee soon after I wake up, so I haven’t made mine yet.

While I was filling the coffee into the Moka Pot, I was thinking of the concept of channelling. Basically, if you try to pack the moka pot too tight with coffee powder, then the steam (that goes through the beans, thus extracting the caffeine) takes the easy way out – it tries to create a coffee-less channel to pass through, rather than do the hard work of extracting coffee as it passes through the layer of coffee.

I’m talking about steam here – water vapour, to be precise. It is as lifeless as it could get. It is the gaseous form of a colourless odourless shapeless liquid. Yet, it shows the seeming “intelligence” of taking the easy way out. Fundamentally this is just physics.

This is not an isolated case. Last week, at work, I was wondering why some algorithm was returning a “negative cost” (I’m using local search for that, and after a few iterations, I found that the algorithm is rapidly taking the cost – which is supposed to be strictly positive – into deep negative territory). Upon careful investigation (thankfully it didn’t take too long), it transpired that there was a penalty cost which increased non-linearly with some parameter. And the algo had “figured” that if this parameter went really high, the penalty cost would go negative (basically I hadn’t done a good job of defining the penalty well). And so would take this channel.

Again, this algorithm has none of the supposedly scary “AI” or “ML” in it. It is a good old rule-based system, where I’ve defined all the parameters and only the hard work of finding the optimal solution is left to the algo. And yet, it “channelled”.

Basically, you don’t need to have got a good reason for taking the easy way out now. It is not even human, or “animal” to do that – it is simply a physical fact. When there exists an easier path, you simply take that – whether you are an “AI” or an algorithm or just steam!

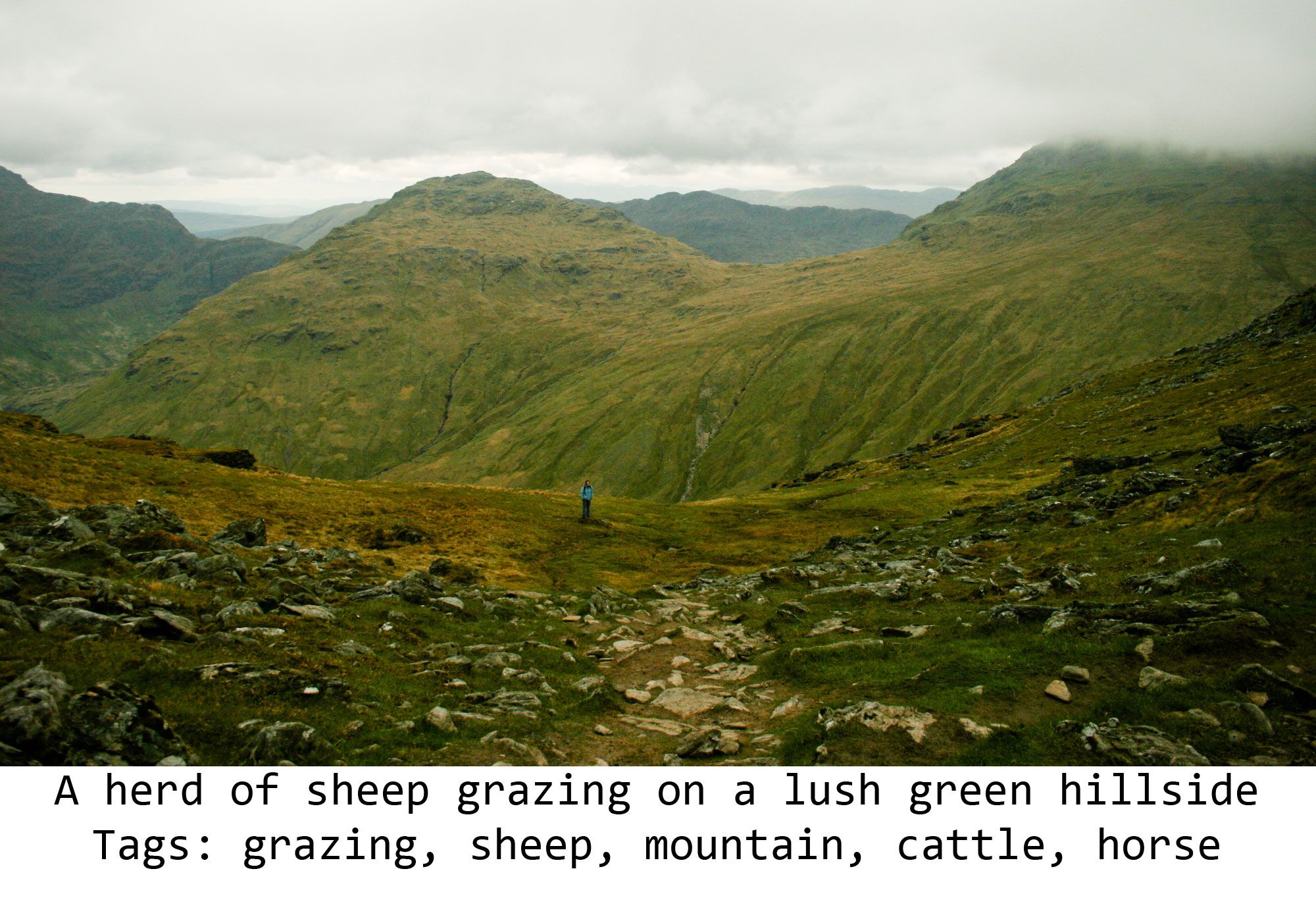

I’ll leave you with this algo that decided to recognise sheep by looking for meadows (this is rather old stuff).