Back in the 1970s, economist Thomas Schelling proposed a model to explain why cities are segregated. Individual people choosing to live with others like themselves would have the macroscopic impact of segregating the city, he had explained.

Think of the city as being organised in terms of a grid. Each person has 8 neighbours (including the diagonals as well). If a person has fewer than 3 people who are like himself (whether that is race, religion, caste or football fandom doesn’t matter), he decides to relocate, and moves to an arbitrary empty spot where at least 3 new neighbours are like himself. Repeat this a sufficient number of times and the city will be segregated, he said.

Rediscovering this concept while reading this wonderful book on Networks, Crowds and Markets yesterday, I decided to code it up on a whim. It’s nothing that’s not been done before – all you need to do is to search around and you’ll find plenty of code with the simulations. I just decided to code it myself from first principles as a challenge.

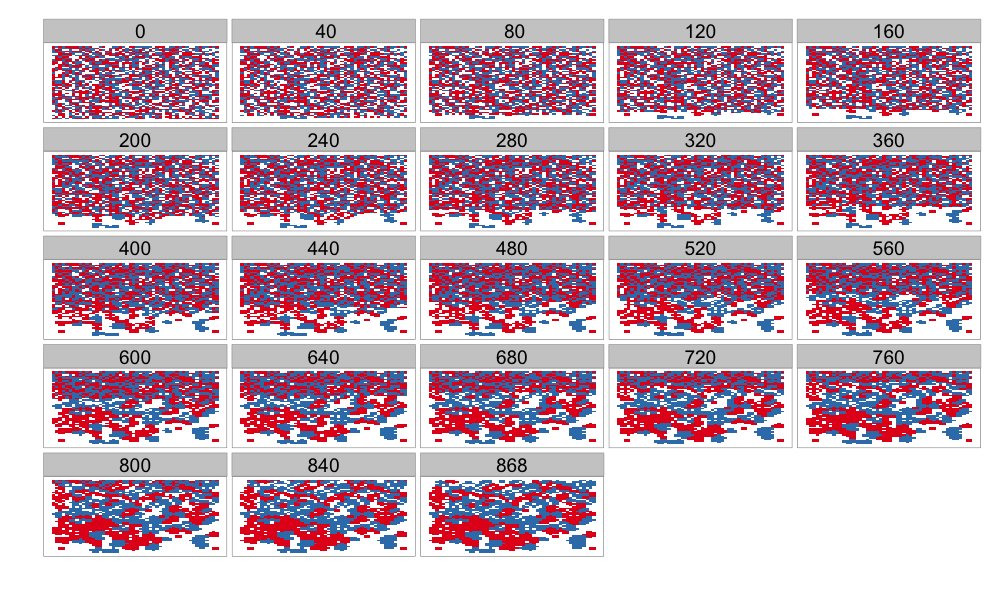

You can find the (rather badly written) code here. Here is some sample output:

As you can see, people belong to two types – red and blue. Initially they start out randomly distributed (white spaces show empty areas). Then people start moving based on Schelling’s rule – if there are less than 3 neighbours of the same kind, you move to a new empty place (if one is available) which is more friendly to you. Over time, you see that you get a segregated city, with large-ish patterns of reds and blues.

The interesting thing to note is that there is no “complete segregation” – there is no one large red patch and one large blue patch. Secondly, segregation seems rather slow at first, but soon picks up pace. You might also notice that the white spaces expand over time.

This is for one specific input, where there are 2500 cells (50 by 50 grid), and we start off with 900 red and 900 blue people (meaning 700 cells are empty). If you change these numbers, the pattern of segregation changes. When there are too few empty cells, for example, the city remains mixed – people unhappy with their neighbourhood have no where to go. When there are too many empty cells, you’ll see that the city contracts. And so forth.

Play around with the code (I admit I haven’t written sufficient documentation), and you can figure out some more interesting patterns by yourself!