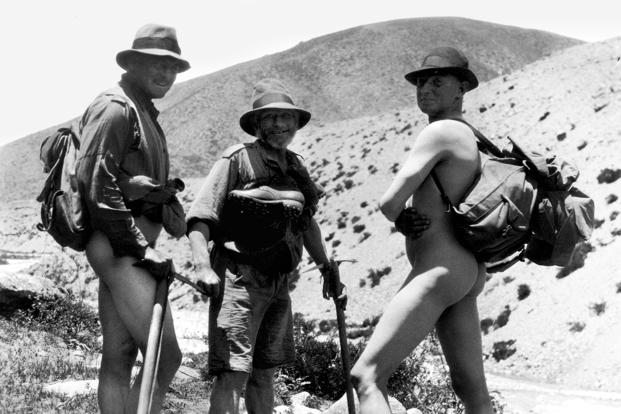

It is not really known if George Mallory actually summited the Everest in 1924 – he died on that climb, and his body was only found in 1999 or so. It wasn’t his first attempt at scaling the Everest, and at 37, some people thought he was too old to do so.

There is this popular story about Mallory that after one of his earlier attempts at scaling the Everest, someone asked him why he wanted to climb the peak. “Because it’s there”, he replied.

In the sense of adventure sport, that’s a noble intention to have. That you want to do something just because it is possible to do it is awesome, and can inspire others. However, one problem with taking quotes from something like adventure sport, and then translating it to business (it’s rather common to get sportspeople to give “inspirational lectures” to business people) is that the entire context gets lost, and the concept loses relevance.

Take Mallory’s “because it’s there” for example. And think about it in the context of corporate metrics. “Because it’s there” is possibly the worst reason to have a metric in place (or should we say “because it can be measured?”). In fact, if you think about it, a lot of metrics exist simply because it is possible to measure them. And usually, unless there is some strong context to it, the metric itself is meaningless.

For example, let’s say we can measure N features of a particular entity (take N = 4, and the features as length, breadth, height and weight, for example). There will be N! was in which these metrics can be combined, and if you take all possible arithmetic operations, the number of metrics you can produce from these basic N metrics is insane. And you can keep taking differences and products and ratios ad infinitum, so with a small number of measurements, the number of metrics you can produce is infinite (both literally and figuratively). And most of them don’t make sense.

That doesn’t normally dissuade our corporate “measurer”. That something can be measured, that “it’s there”, is sometimes enough reason to measure something. And soon enough, before you know it, Goodhart’s Law would have taken over, and that metric would have become a target for some poor manager somewhere (and of course, soon ceases to be a metric itself). And circular logic starts from there.

That something can be measured, even if it can be measured highly accurately, doesn’t make it a good metric.

So what do we do about it? If you are in a job that requires you to construct or design or make metrics, how can you avoid the “George Mallory trap”?

Long back when I used to take lectures on logical fallacies, I would have this bit on not mistaking correlation for causation. “Abandon your numbers and look for logic”, I would say. “See if the pattern you are looking at makes intuitive sense”.

I guess it is the same for metrics. It is all well to describe a metric using arithmetic. However, can you simply explain it in natural language, and can the listener easily understand what you are saying? And more importantly, does that make intuitive sense?

It might be fashionable nowadays to come up with complicated metrics (I do that all the time), in the hope that it will offer incremental benefit over something simpler, but more often than not the difficulty in understanding it makes the additional benefit moot. It is like machine learning, actually, where sometimes adding features can improve the apparent accuracy of the model, while you’re making it worse by overfitting.

So, remember that lessons from adventure sport don’t translate well to business. “Because it’s there” / “because it can be measured” is absolutely NO REASON to define a metric.